|

Iris Hauser was born in 1956 in Cranbrook, British Columbia. She studied at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design in the 1970s, and then came to Saskatoon to study at the University of Saskatchewan. She then moved to Kassel, Germany to study independently for a year before returning to Canada. Hauser has taught art at the Mendel Art Gallery and at the University of Saskatchewan's Certificate of Art and Design program. Iris continues to live and work in Saskatoon.

|

An Artists's Journey: The Beginning

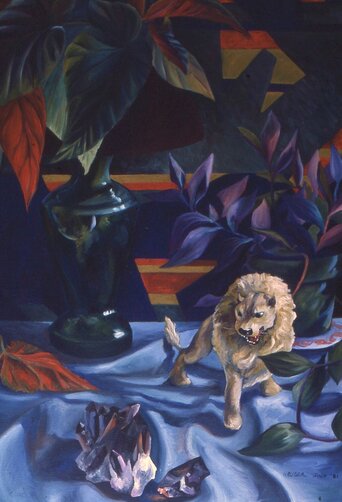

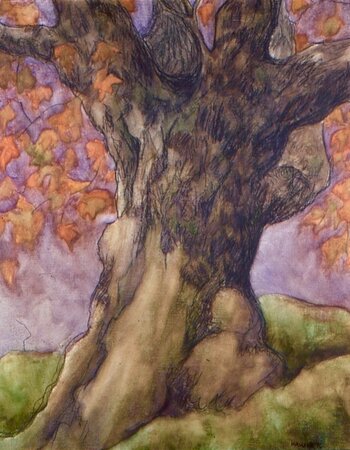

Cedar Tree, 1976

Cedar Tree, 1976

Painting has always been my passion. I loved the great paintings that I found in books, but their technically exquisite, figure based imagery seemed unattainable, and far from my experience. The only art I saw being made locally was landscape painting. So I painted the typical representations of wilderness on camping trips, and at home in Victoria I wandered the neighbourhood drawing and painting. I spent a lot of time in Ross Bay Cemetery, where a wealth of beautiful and varied trees were scattered around the stone and marble monuments. The serenity of the place seeped into me, and perhaps played a part in the development of my future work, which often depicts the cycle of life as a peaceful, circular process. Most of my favourite paintings from this period were of solitary trees with a lot of individuality, basically, tree ‘portraits’. I also painted portraits of my family and friends, trying to get beneath the surface and capture personality and mood.

Although I excelled academically in school, I could never imagine pursuing any other career than art. I had no idea how one could become such a strange creature as a professional artist, but I knew it was what I had to do. There was no internet in those days, so I researched brochures at the library to try to find a good art school. The Nova Scotia School of Art and Design presented itself as a place to gain technical excellence, and my high school art teacher said it had a good reputation, so I applied there. I worked hard as a nurse’s aide evenings and weekends all through grades 11 and 12, saving every penny I could for my future training. In the fall of 1974, I married my life partner, Zach, and together we left BC to cross the country and attend art school. I really enjoyed the city of Halifax with its colourful buildings, the sense of history, and just how different it was from home, but art school was a shock. My dreams of finding answers to all the technical questions I had were crushed at the first introductory class. Our instructor was a pleasant fellow, but he had no interest in or knowledge of painting technique. The new director at the school was Gary Kennedy, and the school had become a leader in the world of conceptual art. As I moved on to first year painting, my instructor employed ridicule and contempt to discourage any kind of realism. I wasn’t then equipped to argue my position philosophically, but my innate stubbornness kept me painting my own way. My frugal nature stopped me from quitting without completing the year, and my father’s teachings of standing up to bullies had me verbally duking it out every day with my deeply loathed instructor. This was a horribly stressful year, and it left me feeling defensive and suspicious of new ideas. I left art school after completing the year, and, although I took a few classes at other institutions, I never completed a Fine Arts degree.

Although I excelled academically in school, I could never imagine pursuing any other career than art. I had no idea how one could become such a strange creature as a professional artist, but I knew it was what I had to do. There was no internet in those days, so I researched brochures at the library to try to find a good art school. The Nova Scotia School of Art and Design presented itself as a place to gain technical excellence, and my high school art teacher said it had a good reputation, so I applied there. I worked hard as a nurse’s aide evenings and weekends all through grades 11 and 12, saving every penny I could for my future training. In the fall of 1974, I married my life partner, Zach, and together we left BC to cross the country and attend art school. I really enjoyed the city of Halifax with its colourful buildings, the sense of history, and just how different it was from home, but art school was a shock. My dreams of finding answers to all the technical questions I had were crushed at the first introductory class. Our instructor was a pleasant fellow, but he had no interest in or knowledge of painting technique. The new director at the school was Gary Kennedy, and the school had become a leader in the world of conceptual art. As I moved on to first year painting, my instructor employed ridicule and contempt to discourage any kind of realism. I wasn’t then equipped to argue my position philosophically, but my innate stubbornness kept me painting my own way. My frugal nature stopped me from quitting without completing the year, and my father’s teachings of standing up to bullies had me verbally duking it out every day with my deeply loathed instructor. This was a horribly stressful year, and it left me feeling defensive and suspicious of new ideas. I left art school after completing the year, and, although I took a few classes at other institutions, I never completed a Fine Arts degree.

Bay of Biscay, 1980

Bay of Biscay, 1980

Over the years, I have often wondered if my career might have been much better if I could have conformed to the system, but in the end, I am content with my choice. Because I didn’t follow the herd, I think I have been able to carve out a path of my own. I have produced a body of work that speaks to contemporary issues, but remains true to my own vision.

After art school, I travelled to New York and Europe for the first time, with the remainder of my art school savings. Finally I was able to see the paintings that had so impressed me from books, but also I had the chance to see vast quantities of work, good, bad and indifferent. I had to concede that mere technical virtuosity was not sufficient to make a painting worth looking at. The endless rooms of utter drivel in the Louvre and other galleries made it clear that great art is not found in polished craft or in realism, but in a kind of conviction that is not restricted to any particular style. Great art is rare, but when you find it, the reward is amazing. It can change how you see the world, and contains such a depth of humanity and connectedness. Seeing these great paintings in a vast range of styles, from Rembrandt to Rothko, encouraged me to continue the struggle.

After art school, I travelled to New York and Europe for the first time, with the remainder of my art school savings. Finally I was able to see the paintings that had so impressed me from books, but also I had the chance to see vast quantities of work, good, bad and indifferent. I had to concede that mere technical virtuosity was not sufficient to make a painting worth looking at. The endless rooms of utter drivel in the Louvre and other galleries made it clear that great art is not found in polished craft or in realism, but in a kind of conviction that is not restricted to any particular style. Great art is rare, but when you find it, the reward is amazing. It can change how you see the world, and contains such a depth of humanity and connectedness. Seeing these great paintings in a vast range of styles, from Rembrandt to Rothko, encouraged me to continue the struggle.

An Artist’s Journey: Finding my Path

An Artist’s Journey: Going the Distance

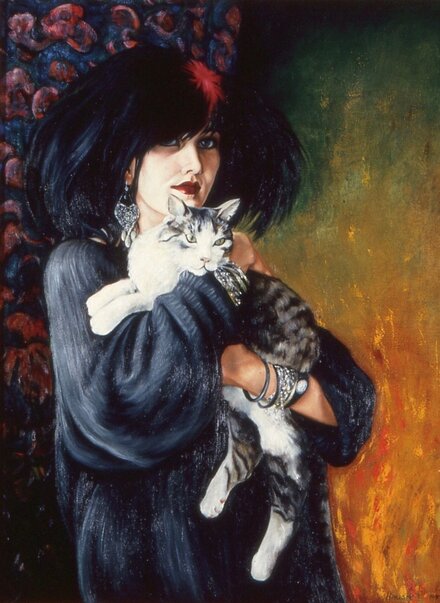

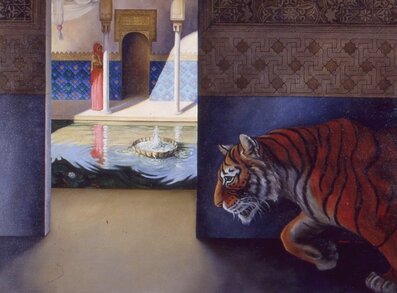

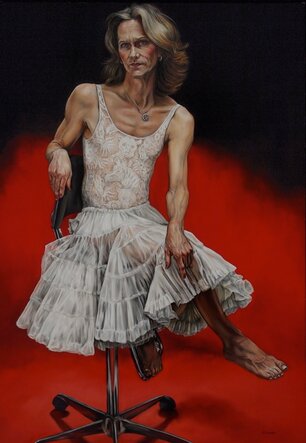

The Changeling, 2012

The Changeling, 2012

These two streams of paintings have continued in my work. Complex narratives in staged tableaux have evolved as I have become more technically skilled, and have grown and deepened in content with my growth as a person. The study of humanity through the lens of the individual has also continued, most recently in my series of portrait studies of gender identity and presentation in the touring exhibition ‘Dress Codes’.

My latest efforts continue these explorations. In 2018, I will be mounting an exhibition of narrative works at the Mann Gallery in Prince Albert. Many are related to literary sources, such as Alice in Wonderland and the Bible, books which have entered the collective consciousness with powerful and profound metaphoric and symbolic imagery.

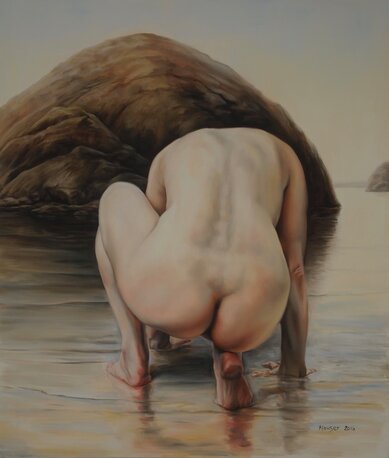

I am also working on a series of paintings of the body seen as a form in space, literally figure and ground studies. As I begin to work through this, I see multiple directions emerging. The Woman, the first in this series, depicts the womanly body, fertile, beautiful and strong; the source of life, grounded in the earth, and paired with the generative imagery of the ocean. The woman and the rock present a dialogue of form, both roundly solid and centered on the spine.

My latest efforts continue these explorations. In 2018, I will be mounting an exhibition of narrative works at the Mann Gallery in Prince Albert. Many are related to literary sources, such as Alice in Wonderland and the Bible, books which have entered the collective consciousness with powerful and profound metaphoric and symbolic imagery.

I am also working on a series of paintings of the body seen as a form in space, literally figure and ground studies. As I begin to work through this, I see multiple directions emerging. The Woman, the first in this series, depicts the womanly body, fertile, beautiful and strong; the source of life, grounded in the earth, and paired with the generative imagery of the ocean. The woman and the rock present a dialogue of form, both roundly solid and centered on the spine.

The Woman, 2016

The Woman, 2016

Another series will explore the cliche of the female form paired with decorative floral imagery. I am intrigued by these persistent tropes, as they express some fundamental concepts of the feminine, which I hope to reinvigorate with a respectful and sincere re-imagining, adding strength and individuality to the classic idealized image of the objectified woman.

The advantage of having developed outside the current art system, but aware of it, is that I know the marked paths, but feel unrestricted by their boundaries. I may not get through to a successful career as quickly as those who follow the set route, I may even get lost in the underbrush forever and never ‘arrive’ at all, but I have the potential to discover something original and amazing. On a good day, when concepts and technique fuse to produce an image that gives me that clarion ring of powerful truth, that jolt to the heart and brain that I associate with great art, then I know I am right where I want to be, and all is well in my world.

The advantage of having developed outside the current art system, but aware of it, is that I know the marked paths, but feel unrestricted by their boundaries. I may not get through to a successful career as quickly as those who follow the set route, I may even get lost in the underbrush forever and never ‘arrive’ at all, but I have the potential to discover something original and amazing. On a good day, when concepts and technique fuse to produce an image that gives me that clarion ring of powerful truth, that jolt to the heart and brain that I associate with great art, then I know I am right where I want to be, and all is well in my world.